DMSC Devlog: Week 2 - Made for Walking

One week into a programming class and the training wheels are coming off! After last class's warm-ups with LOGO, a language designed with sixth-graders in mind, we have graduated to the very adult JavaScript library p5.js. It's taking some getting used to, but a semester of learning Processing-style Java last year has proven immensely helpful - plus, it's nice to not have to write your code perfectly before you run it. Most of our focus is on generating visuals, starting with the most basic functions of creating a canvas, drawing shapes, and making pictures change with if statements and for loops. Even with just these tools, the possibilities are endless!

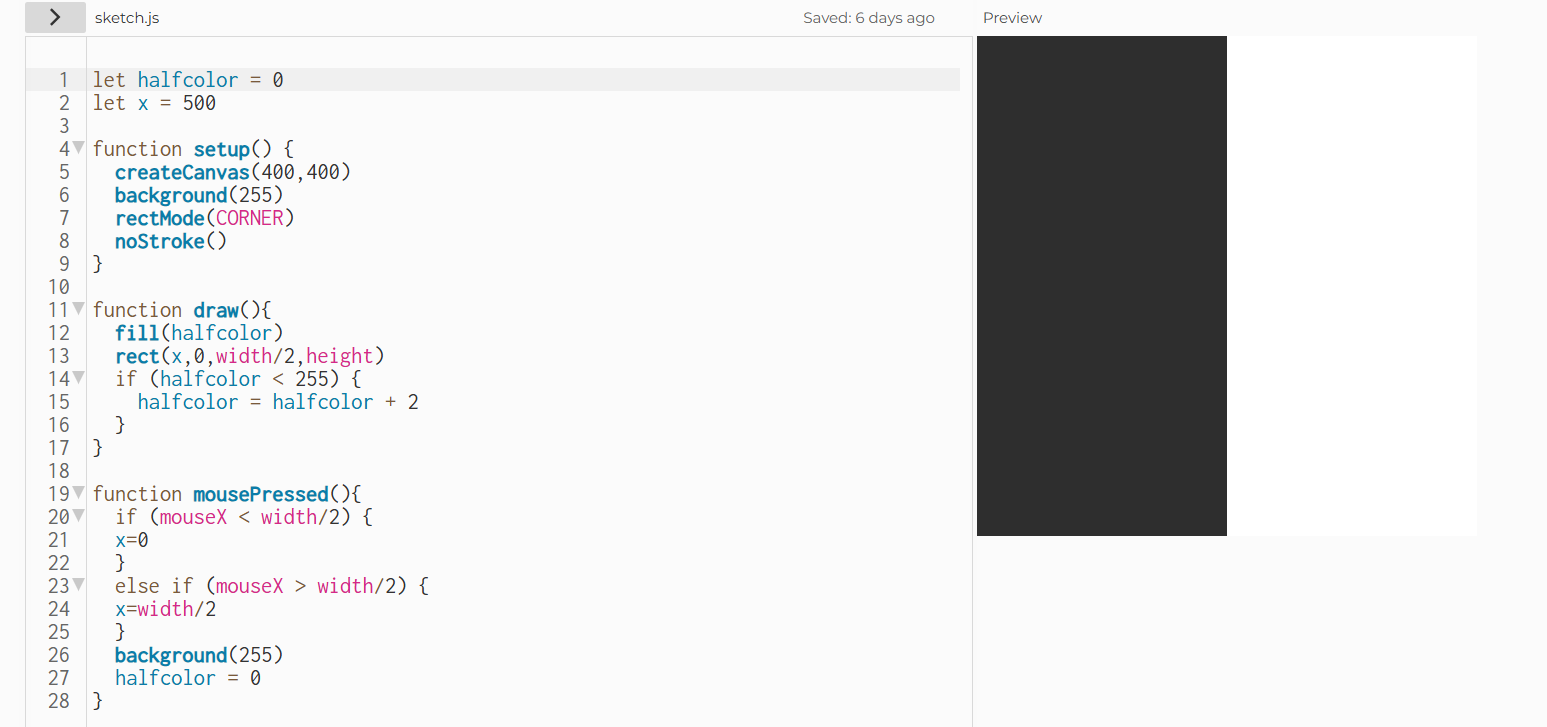

Step 1 of the p5 journey was making a black rectangle appear on different sides of our canvas.

Basic, but we have to start somewhere.

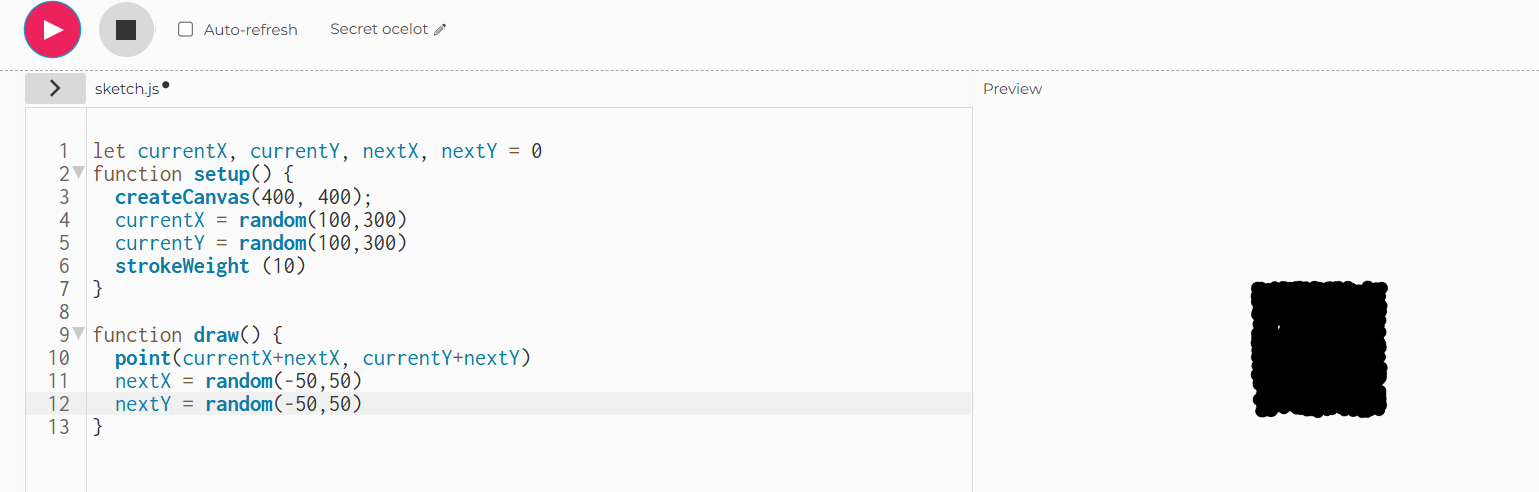

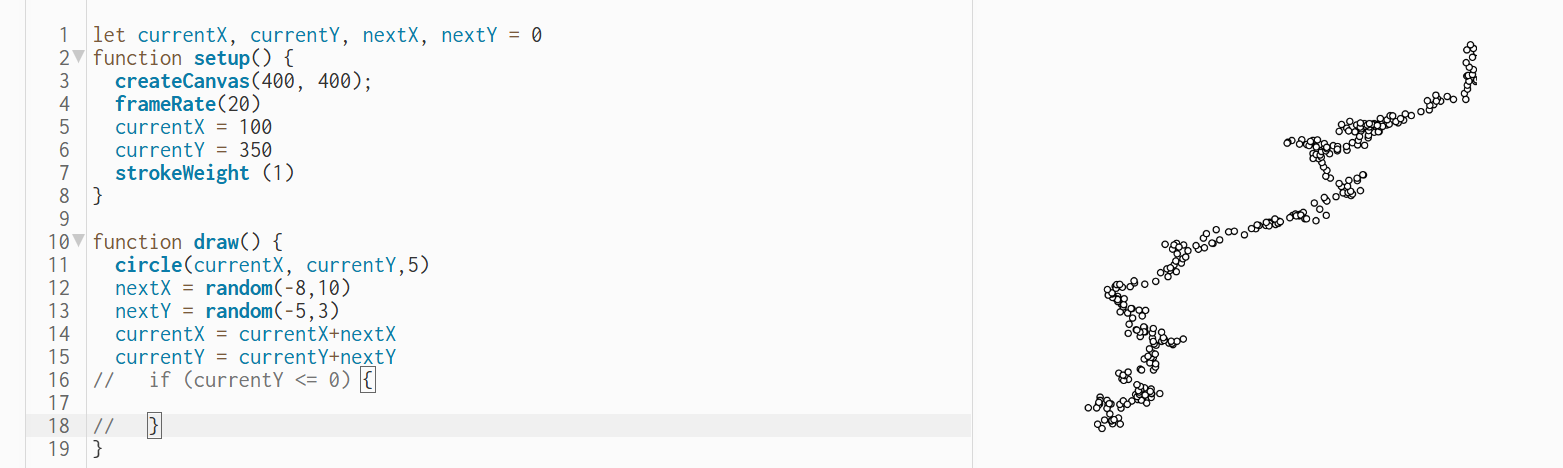

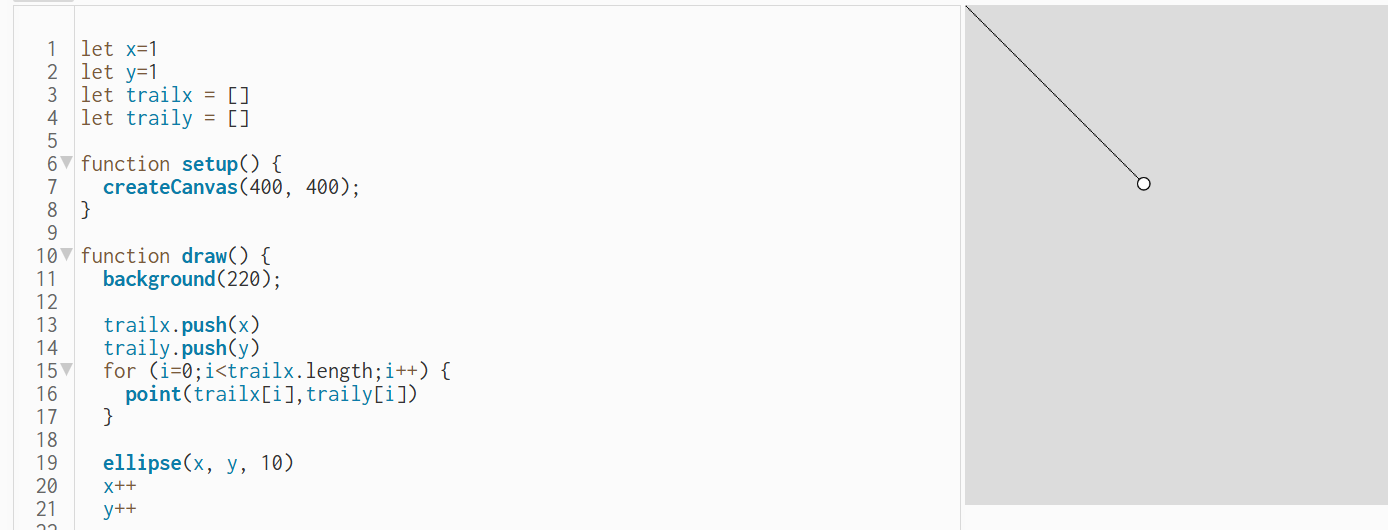

Step 2 was making a circle go for a "random walk" from one corner of the canvas to the other.

Maybe the training wheels aren't off quite yet.

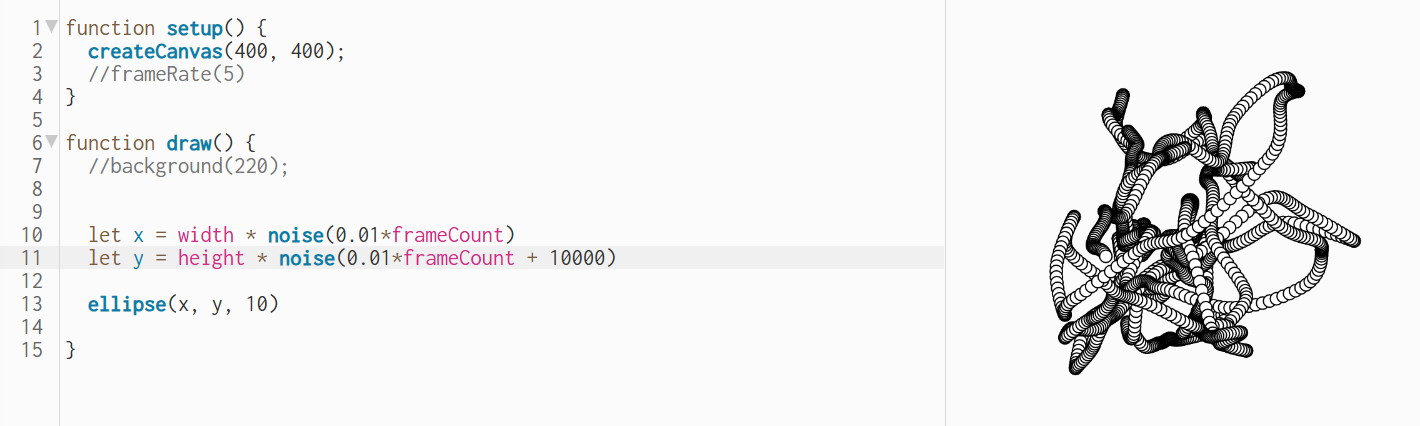

Step 3 is where things get interesting. We are introduced to Perlin noise, the algorithm developed by Ken Perlin to make the smoke in Tron look smokier. In the random walk, each point is a random distance from the last; we can skew the range of randomly generated numbers to favor a positive distance (generating a point downwards or to the right) or negative distance (upwards or to the left), but the result is a chaotic jittery zigzag of a path. Each random number generated using Perlin noise, however, is based on the number that came before it, making for much more gentle variations between each value. Look at the curves!

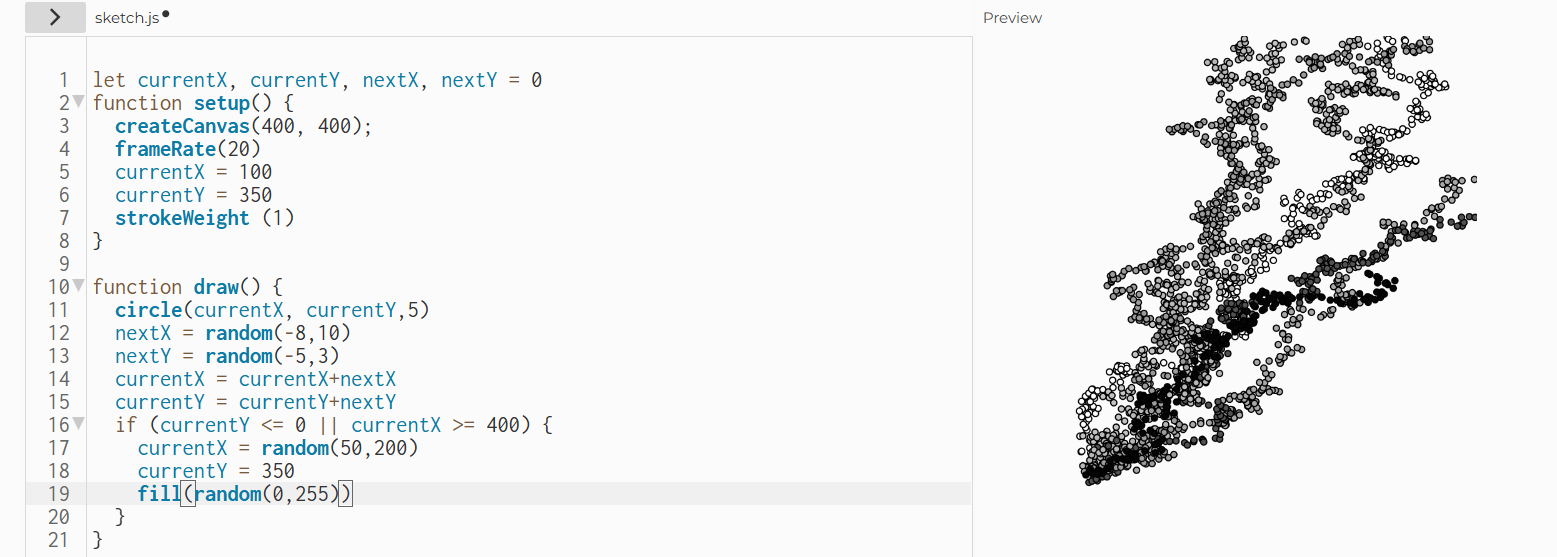

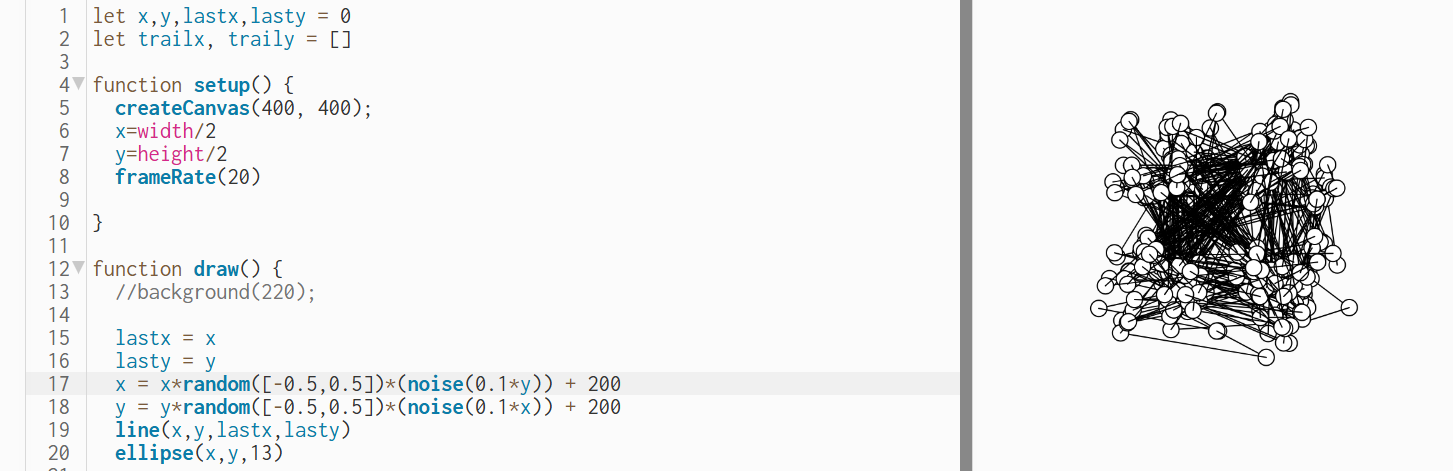

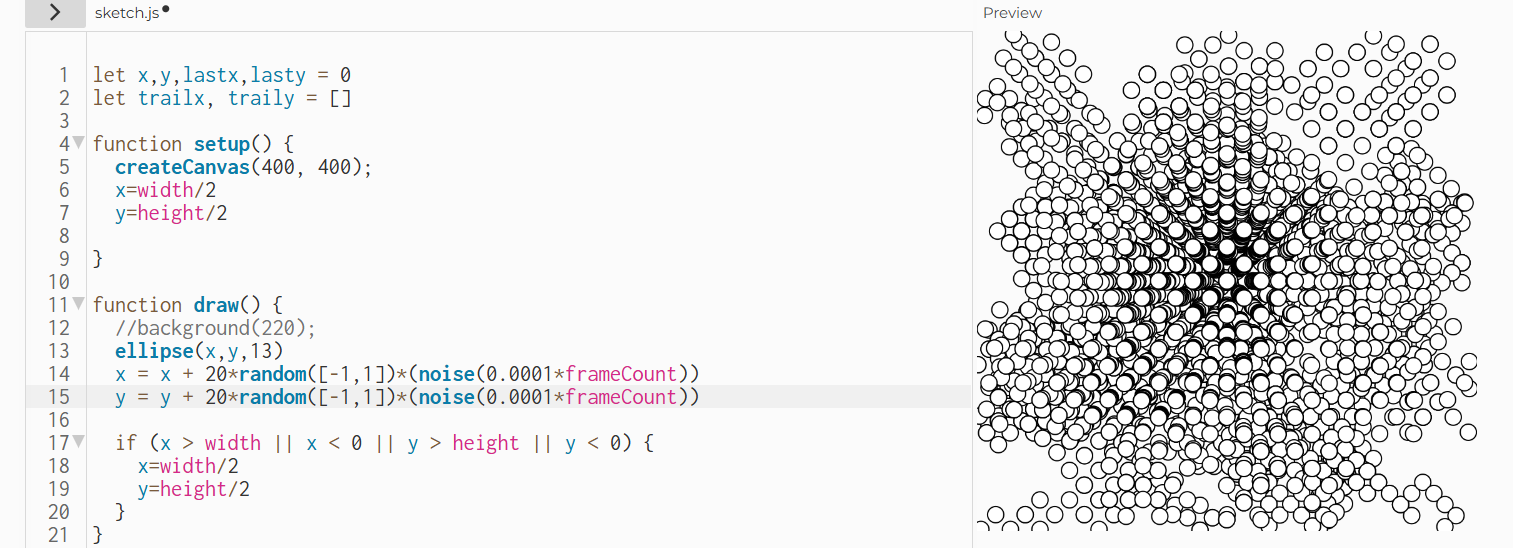

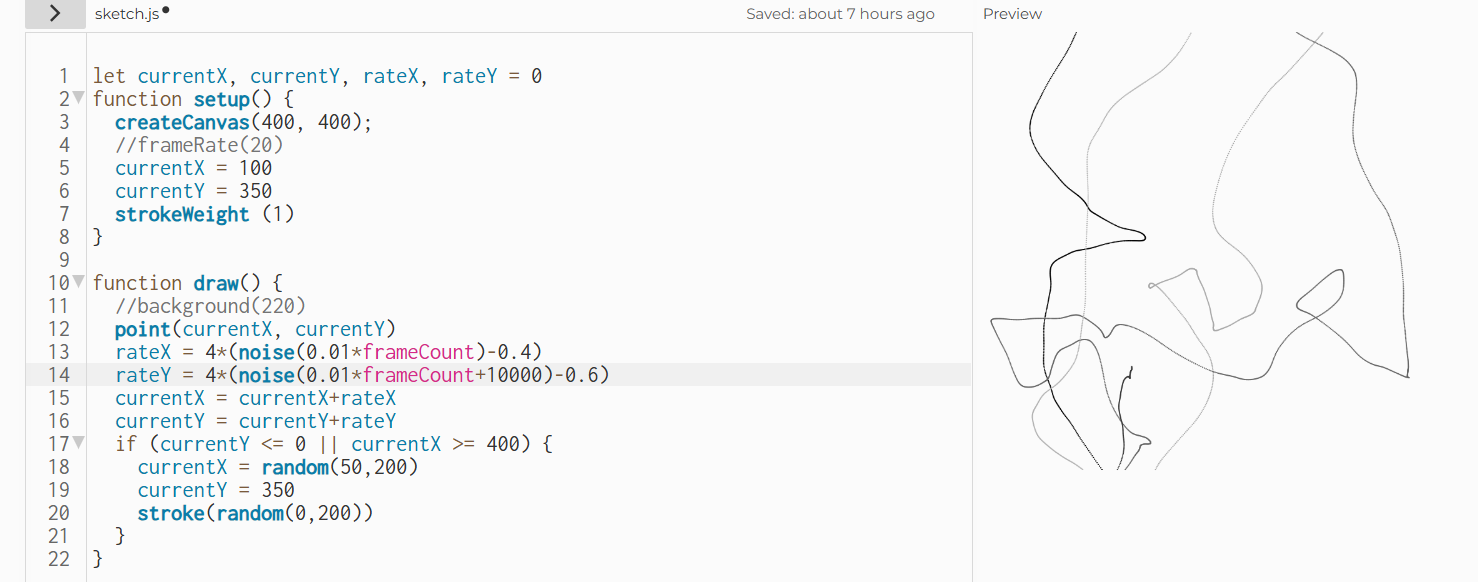

We are now tasked with adding Perlin noise to our random walk generator. The idea is to get a more natural, less overly-caffeinated walk. Here are several of my attempts:

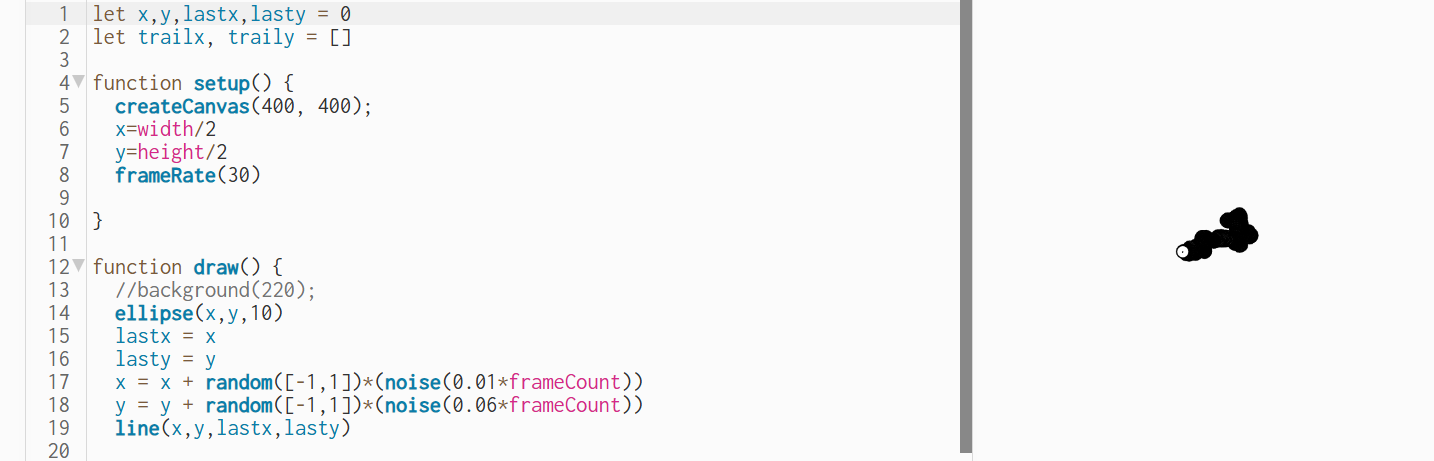

All the final program was missing was a ball to do the walking. And a trail marker a different thickness than the ball.

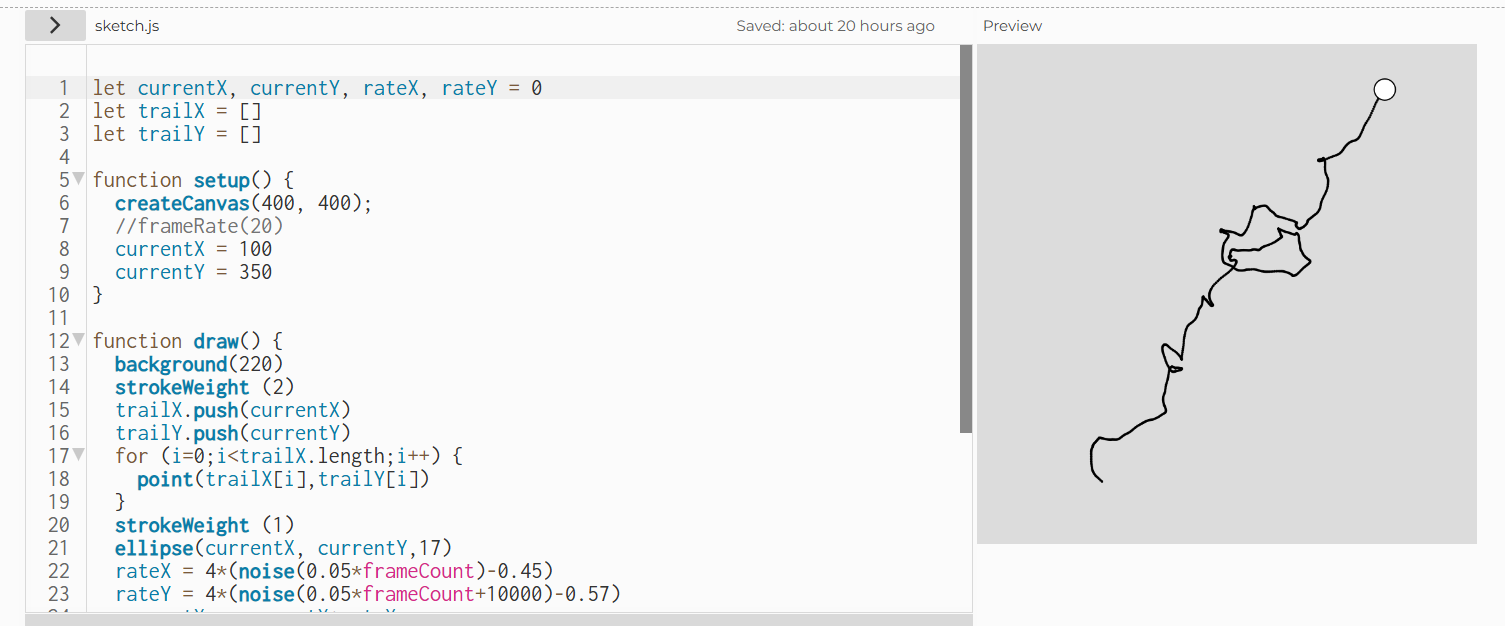

The best I've got - an array records every point the ball passes through, then redraws every point on the path, every frame. Just don't run it for too long.

The best I've got - an array records every point the ball passes through, then redraws every point on the path, every frame. Just don't run it for too long. Similarly to the random number generator in the OG random walk, "rateX" tends towards positive numbers (to the right) while "rateY" tends towards negative numbers (up).

Similarly to the random number generator in the OG random walk, "rateX" tends towards positive numbers (to the right) while "rateY" tends towards negative numbers (up).And we've done it! No flashy designs, no text or walls to bump into or colorful floating iceberg, just hours of messing with arrays and percentages. I'll see if I can't stick a smiley face or a picture of an ice cube on the end of it to top it off.

This Perlin noise stuff is cool! I don't totally understand (at all in any capacity) how adding more dimensions to the noise() function works, but this whole exercise seems like a good, if time-consuming, starting point. Looking forward to using it again maybe eventually!

-Rafi

Drawing, Moving, and Seeing with Code Devlogs

| Status | In development |

| Category | Other |

| Author | rafi.pdf |

More posts

- DMSC Devlog: Week 8 - Video SynthesisJun 03, 2025

- DMSC Devlog: Week 6 & 7 - Climate ChangeApr 30, 2025

- DMSC Devlog: Week 5 - Special Delivery!Apr 23, 2025

- DMSC Devlog: Week 4 - Random SeedingApr 12, 2025

- DMSC Devlog: Week 3 - Class WorkFeb 18, 2025